After disc surgery, muscles may sometimes contract when they shouldn't. This can feel odd or mildly irritating, but when accompanied by pain—or if severe—it may even lead to paralysis. While these symptoms are fairly common and can cause anxiety, they rarely develop into serious medical problems.

Unwanted muscle contractions can take various forms, and it's often difficult to pinpoint a clear cause or classify them precisely. The terms used to describe them can be confusing, with overlapping meanings that make things more complicated.

For instance, the word spasm is frequently used in vague ways. It's often applied to describe musculoskeletal pain even when no actual muscle contraction is involved. Similarly, the word cramp originally refers to sudden, exercise-related muscle spasms but is now loosely used in a wide range of contexts. These terms are often used out of habit to explain pain that arises without an obvious cause.

When cramps or spasms feel particularly intense, people often blame "muscle tension." But this explanation doesn't always accurately reflect the real symptoms, and in many cases, it's unclear whether the contraction is partial or full-body.

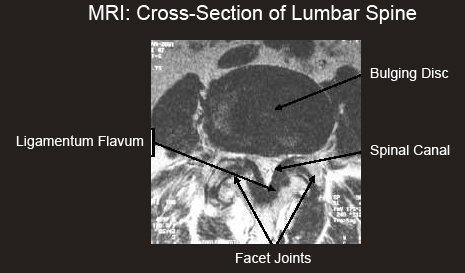

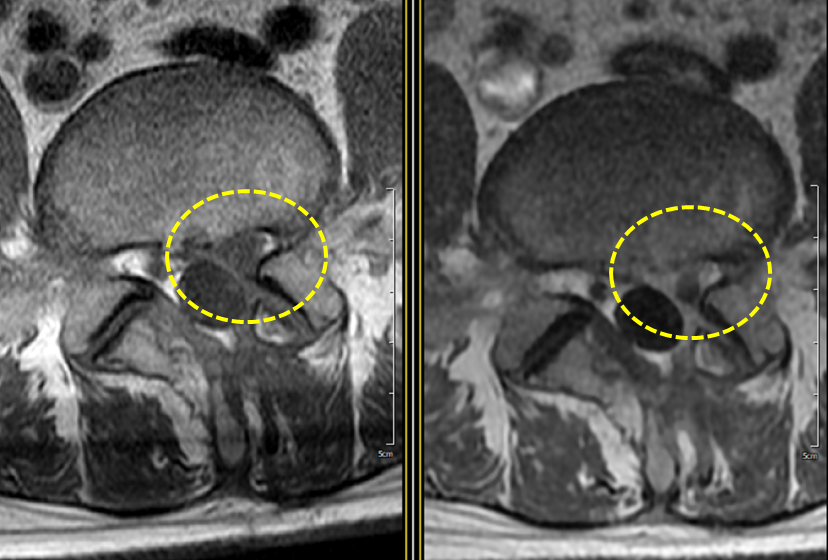

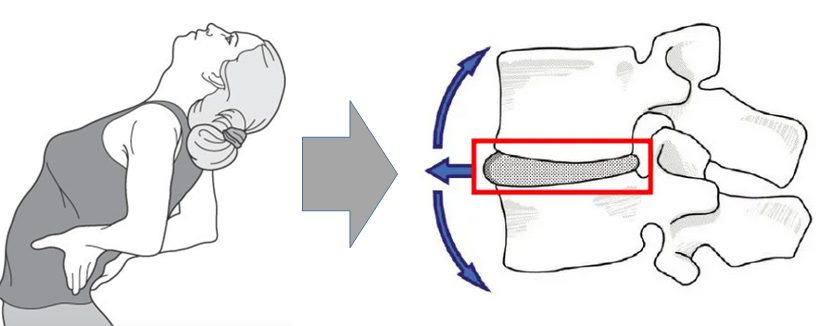

These contractions may be closely related to spinal disc issues. When a disc presses on a nerve, the connected muscles can react abnormally, leading to spasms, tremors, or involuntary contractions. Lumbar disc problems, in particular, can trigger these reactions along the nerve pathways that run into the legs or buttocks. This can interfere with daily activities and sometimes result in severe pain. If such symptoms are mistaken for simple muscle strain and dismissed, treatment might be delayed—so accurate diagnosis is important.

Unwanted muscle contractions are real, and in some cases, extremely painful. Many people have experienced dramatic episodes, such as menstrual cramps, sudden calf cramps during exercise, or intense foot cramps during sleep. These examples show that even seemingly minor muscle contractions can cause disproportionately intense pain. When nerve compression from a disc is the cause, the resulting pain may be much deeper and more complex than that of a typical muscle spasm.

|

| Tremors and Involuntary Muscle Contractions |

Basics of Muscle Contraction

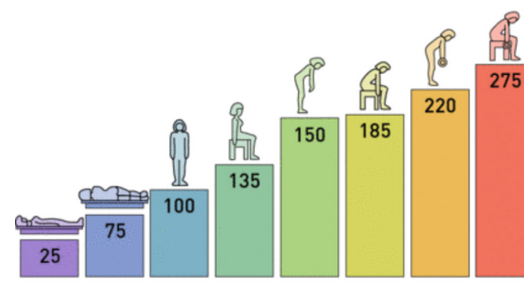

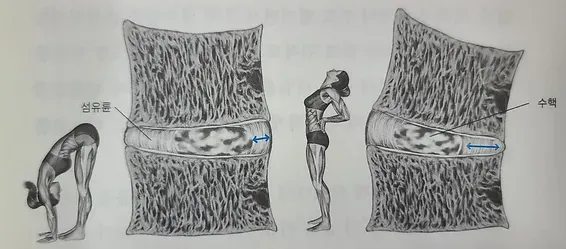

Muscle movement is driven by bundles of protein filaments that operate much like Velcro. However, rather than simply sticking together, countless tiny hooks bend in one direction, release, reattach, and bend again in a repeated cycle. This motion is similar to the way an inchworm crawls—pulling one part of its body forward while anchoring the other. Muscle proteins function in a comparable way, but at an unimaginably fast and microscopic level.

As these microscopic protein actions repeat countless times, they result in visible muscle contraction. If you magnify this process, you can begin to understand how we’re able to move an arm or walk with our legs. To learn more about this fascinating mechanism, it can be helpful to explore how micro-muscles and sarcomeres work.

Yet when we look at this contraction process from a biochemical perspective, it becomes incredibly complex. Many aspects are still not fully understood, with some mechanisms appearing to operate at extremely fine and delicate levels. Additionally, there are numerous ways in which this process can go wrong, and the effects are often unpredictable and highly intricate.

What causes sharp pain in the lower back?

Symptoms often described as "lower back spasm" or "pulled back" are merely poetic or informal ways to depict the sudden onset of intense lower back pain. In reality, the causes of back pain are highly diverse, and accurately identifying the root cause remains one of the most challenging tasks in medicine. For this reason, I have written extensively on back pain over the past several years and have even authored books on the subject.

Sudden back pain is not a simple symptom but rather a single outcome that can result from various causes. The greater the intensity of the pain, the more people tend to associate it directly with specific mechanisms like injury or spasm; however, the severity of pain is not a reliable indicator for determining its cause.

Back pain often feels like a spasm because the pain itself triggers a reflexive muscle response. In other words, when pain occurs, the body unconsciously braces or tightens. This reaction is a consequence of the pain, not the cause.

This acute stiffness eventually leads to restricted movement and can sometimes feel like a muscle spasm. However, the underlying cause is far more complex and cannot be simply explained as “a cramp.”

Protective muscle spasm, or "muscle splinting"

The concept that muscles act as protective spasms or serve as a kind of “muscle splint” has not yet been clearly proven. Muscles respond in various ways depending on the situation, and their behavior is complex and difficult to predict. The body sometimes exhibits competing and confusing reflexes, meaning it is literally unsure how to respond. These reactions can change continuously depending on the environment and over time.

However, one clear fact is that excessive muscle contraction around fragile or injured tissues is never desirable. For example, if muscles attached to a severely fractured bone go into strong spasms, this can actually hinder recovery or cause additional damage to healthy tissue. Excessive contraction can ultimately cause bigger problems rather than protecting the tissue.

So which scenario is more likely? While not simple spasms, muscle responses that are in some form “protective” or sometimes the opposite definitely exist. In fact, we can think of at least three such examples:

-

Reflexive muscle tension — muscles unconsciously tighten when sensing pain or threat.

-

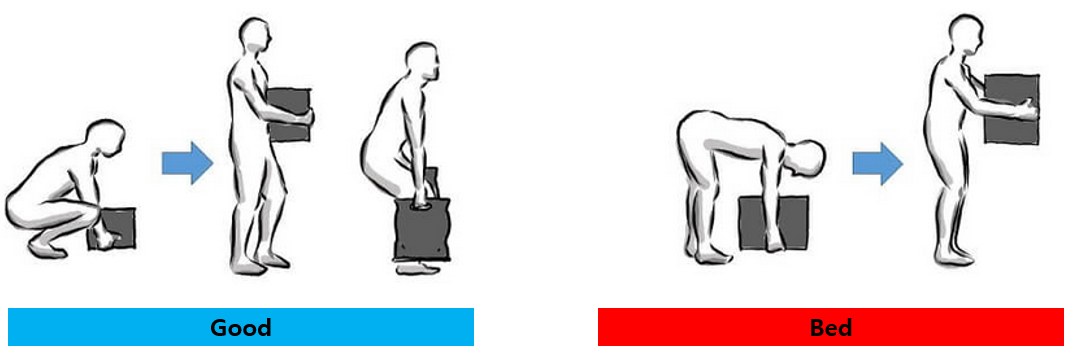

Asymmetric muscle compensation — other muscles overwork to avoid the injured area.

-

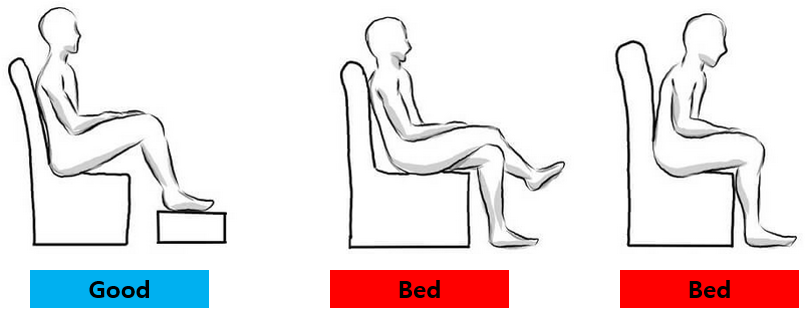

Pain-avoidance movement — certain muscles contract persistently to avoid specific postures or motions.

These reactions aren’t clearly classified as “spasms,” but in some ways, they function with the intent to protect tissue. At the same time, these protective responses can become harmful or develop into chronic problems.

What does it mean to feel tight and stiff?

Our muscles never fully relax unless paralyzed; they maintain a slight, continuous contraction and tension at all times. This basic muscle tone is essential for maintaining posture and supporting the body. Muscle contraction is not simply an on/off switch but varies in intensity and degree. Even the same level of tension can feel different depending on the individual and their physical condition. Therefore, descriptions like “tight” or “stiff” are subjective sensations reflecting discomfort in muscle tone beyond usual levels. The concept of a “normal muscle tone” is difficult to define, and objective, reliable measurements are nearly impossible. Although there are devices to measure muscle tension, they are very rare, and most assessments rely on subjective judgment, like that of massage therapists.

The texture of healthy muscles varies widely and does not necessarily correlate with common pain or stiffness. The feeling of “aching” is also subjective and may be related to other issues such as muscle spasms.

“Stiffness” does not directly indicate tissue condition nor does it strongly correlate with objective changes like reduced range of motion. It is usually a mild form of discomfort and should not be regarded as an accurate indicator of muscle tension.

Muscle Cramps: Tremors and Vibrations Caused by Fatigue — An Interesting Muscle Phenomenon

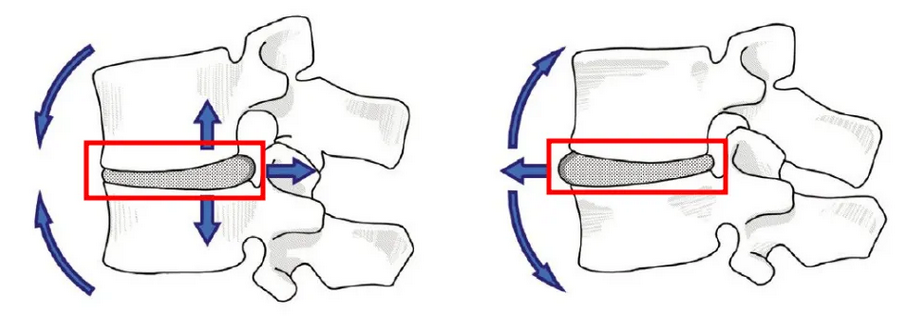

Muscle fibers do not contract all at once as commonly believed. Instead, each motor nerve is divided into small groups called “motor units.” Rather than all motor units contracting simultaneously, these groups contract alternately like pistons. Because many motor units are continuously going through different phases of contraction and relaxation, we experience smooth and natural muscle movement.

However, there is an interesting exception. When muscles become too fatigued and multiple motor units fail to contract properly, there aren’t enough active motor units for smooth contraction, causing the switching system to malfunction. This results in muscle trembling or rippling waves during intense exercise.

The Reality of Muscle Relaxants

Using muscle relaxants may seem like a good idea, but in reality, they often are not as effective as expected. A common over-the-counter muscle relaxant is methocarbamol (such as Robaxin), but studies have shown that its effect is often no greater than that of a placebo.

Prescription muscle relaxants like carisoprodol also tend to have weak effects, and sometimes, misinformation that these drugs act as stimulants can even increase feelings of tension.

Muscle tone is controlled primarily by the brain, and it is difficult to completely relieve muscle tension with medication alone.

Conclusion: Understanding and Managing Symptoms is the Key

Tremors, spasms, and involuntary muscle contractions after disc surgery are common and often distressing. However, these reactions do not necessarily indicate a serious underlying problem. During the recovery process, the body may respond in various ways to protect itself or to regain balance.

The important thing is not to ignore these symptoms or overreact to them, but rather to try to understand the signals the body is sending. If needed, a professional diagnosis can help identify the cause, and symptoms can often be managed through a combination of exercise, physical therapy, or medication.

Ultimately, recovery is not just about treatment—it's about listening to the body and learning to adjust. What we need is not suppression, but regulation; not fear, but understanding. Through this process, the body gradually regains its balance, and we can return to a healthier, more stable daily life.